Free PSA:total PSA ratio

Dysuria, rectal bleeding, impotence, erectile dysfunction

Prostate Radiation side effects

Dr. Sam Kumarasena: And the second to last, let’s move on to prostate radiation. What are the acute side effects? We already kind of mentioned that people aren’t really going to see burns with it, so I guess that’s one win!

Dr. Shreya Trivedi: Yep!

Dr. Daphna Spiegel: A lot of the side effects that you can experience have to do with what’s nearby. And so for a prostate patient I might say, you might find you’re going to the bathroom more frequently, urinating more frequently, sometimes even having more frequent bowel movements or looser stools things like that.

Dr. Sam Kumarasena: We’re back on that location-dependence theme here! The acute side effects are gonna involve what’s nearby the prostate, the bladder, the rectum, basically anything in the pelvis. Now, how about the late side effects?

Dr. Matthew Abrams: Late side effects. Uh, so things like, um, uh, erectile dysfunction, uh, is a ongoing issue that, uh, can happen after any, um, uh, treatment to the prostate, whether that be surgery or radiation. Sometimes patients, uh, present with, uh, rectal bleeding. That can be associated with the late complication from, from radiation to the prostate. Suffice it to say that if, uh, a patient showed up with prior prostate radiation in your clinic with rectal bleeding, you would absolutely wanna work up that rectal bleeding for any other reason. I would not, um, write it off as related to radiation. That would be almost a diagnosis of exclusion. You would want to rule that up for work that up for, for, you know, as you normally would, um, whether that be, uh, you know, a rectal exam, colonoscopy, et cetera, uh, to make sure you’re not missing any other underlying malignancy, for example.

Dr. Sam Kumarasena: Aye aye, Captain! The diagnosis of exclusion is hammered home yet again.

Dr. Shreya Trivedi: But, wait a minute, bones are also in the pelvis too, so how does prostate or pelvic radiation affect the bones?

Dr. Daphna Spiegel: Anytime we radiate the pelvis, there’s always the possibility long term that could cause issues with the fracture. Really, it’s true for any bone, but we think about it a lot because obviously you know have really important bones that live in your pelvis. And so we think about that and counsel patients that they may be more likely to develop a hip fracture down the road if they’ve gotten a lot of radiation in this area.

Dr. Sam Kumarasena: And as a little aside here, I looked into it, to see if there is anything to prevent some of these pelvic fractures and unfortunately, our interventions, things like calcium and vitamin D supplements, or even bisphosphonates, nothings really been shown to be effective in preventing these fractures.

Dr. Shreya Trivedi: Yeah, bummer, it’s surprising given bisphosphonates aren’t, but it’s good to know! So let me try to summarize prostate radiation side effects, big picture ones. Because radiation is often deeper, we are going to see collateral damage to nearby organs, like prostatitis, cystitis and so on. As well as seeing pelvic insufficiency fractures.

Dr. Sam Kumarasena: One last things that came up about prostate radiation side effects, do we see these prostate radiation side effects with all the different types of radiation? This’ll actually be a throwback to part 1, in which we learned that patients with prostate cancer can either get, external beam radiation therapy, OR brachytherapy, with a radioactive source placed at or in the tumor.

Dr. Shreya Trivedi: Yeah so talking to our experts, it turns out BOTH external beam and brachytherapy can produce similar local side effects, think about the cystitis and proctitis that we just talked about. But, because with brachytherapy, the radiation stays closer to the tumor, brachytherapy is going to have a lower risk of affecting organs further away, like the bone. So that means patients getting brachytherapy are going to have a lower risk of pelvic fractures than those getting external beam radiation.

MKSAP

47 years old and just got mri results back. Not looking good

Just got these results. Being set up with a urologist to discuss next steps. Is this as bad as it looks?

History: Age 47, prostatitis (which report seems to confirm) since my early 20s with really high psa levels which usually dropped after antibiotics. I don't think I have ever had a "normal" PSA result. This is pretty scary to say the least as I am married and have 2 kids under 2 years old.

Is this lesion small? Does the report indicate it has protruded, is bulging or it i unclear? Any advice, insight or words of wisdom would be appreciated.

REPORT:

impression:

multiparametric mri positive for significant or index lesion, intermediate or high grade neoplastic disease.

peripheral zone demonstrates a focal concordant lesion within the lateral and posterolateral aspect of the left prostate base highly concerning for clinically significant disease with findings suggestive of extracapsular extension. seminal vesicles appear uninvolved.

transition zone demonstrates no significant change of bph in a normal size gland.

no osseous lesions or adenopathy appreciated.

tissue sampling recommended.

pi-rads category 5.

1 = very low (clinically significant cancer highly unlikely)

2 = low (clinically significant cancer unlikely)

3 = intermediate (clinically significant cancer equivocal)

4 = high (clinically significant cancer likely)

5 = very high (clinically significant cancer highly likely)

history:

current psa 57.9 ng/ml

prior trus biopsy: none.

comparison study: none

technique: multiparametric mri imaging of the prostate performed on the siemens 3t verio open bore pre and postcontrast. multiplanar high-resolution t2 weighted imaging. t1 dynamic contrast enhancement (dce) during the administration of 10 cc of intravenous vueway. diffusion weighted imaging (dwi). adaptive diffusion coefficient (adc) mapping. three dimensional (3-d) contouring of the prostate with postprocessing on the siemens syngovia independent workstation.

findings:

prostate volume = 23 cc

psa density = 2.5 ng/ml/cc

peripheral zone:

linear and wedge shaped areas of t2 hypointensity throughout the peripheral zone consistent with inflammation/prostatitis.

lesion 1:

- size: 15 x 17 x 17 mm

- location: lateral posterolateral left base, from 3 to 5 o'clock.

concordant abnormality with restricted diffusion, adc values ranging from 320-600 and high signal intensity on 1400 imaging. asymmetrical focal rapid iv contrast enhancement on dce imaging. findings best seen on t2 axial image 18, coronal image 15, sagittal image 21.

extraprostatic tumor extension: there is extracapsular bulge and irregularity at the site of the lesion highly concerning for gross extracapsular extension

- pi-rads: 5, clinically significant cancer highly likely to be present.

transition zone:

no significant changes of bph

no focal concordant transition zone abnormality.

seminal vesicles: seminal vesicles appear uninvolved

urinary bladder: the bladder is predominately decompressed

pelvic lymph nodes: no enlarged or morphologically abnormal lymph nodes.

suspicious bone lesions: none.

other incidental findings: none.

Amboss

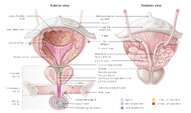

Epidemiology

- Incidence: following skin cancer (i.e., melanoma and nonmelanoma combined) most common cancer in men in the US [1]

- Mortality: in 2020, second leading cause of cancer deaths in men in the US (after lung cancer)

Risk factors

- Advanced age (> 50 years) [1][2]

- Family history

- African-American descent

- Genetic disposition (e.g., BRCA2, Lynch syndrome)

- Dietary factors: high intake of saturated fat, well-done meats, and calcium

Clinical features

Symptoms

- Typically asymptomatic

- Early prostate cancers are typically detected during screening tests.

- Some prostate cancers are found incidentally (incidental prostate cancer).

- Patients may present with features of complicated lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), including: [5]

- Urinary retention

- Hematuria

- Incontinence

- Flank pain (due to hydronephrosis)

- Advanced prostate cancer can manifest with:

- Constitutional symptoms: fatigue, loss of appetite, clinically significant unintentional weight loss

- Features of metastatic disease; examples include:

- Bone pain (due to bone metastasis, especially in the lumbosacral spine)

- Neurological deficits (e.g., due to vertebral fracture causing spinal cord compression)

- Lymphedema (caused by obstructing metastases in the lymph nodes)

Digital rectal examination (DRE) [6][7][8]

- May be normal in early disease or if the cancer is located in areas of the gland that are not palpable on DRE [9]

- Features suggestive of prostate cancer include:

Diagnostics

Approach

- Suspect prostate cancer in patients with elevated PSA levels detected on routine screening and/or abnormal findings on DRE.

- Consider adjunctive PSA testing (e.g., free PSA:total PSA ratio, PSA density, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3 levels) before performing a biopsy.

- Confirm the diagnosis on image-guided prostate biopsy.

- Stage prostate cancer to determine the appropriate management and prognosis.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels

- Indications

- Suspected prostate cancer

- Monitoring for recurrence following treatment of prostate cancer

- Screening for prostate cancer (controversial).

- Interpretation [11][12]

- Other causes of elevated total PSA: BPH, UTI, prostatitis, prostatic trauma or manipulation (including DRE) [14]

Urinalysis [17][18]

- Should be performed as part of the initial workup of LUTS and to rule out differential causes of elevated PSA

- Urinalysis is typically normal in patients with prostate cancer.

- Pyuria and/or bacteriuria in a patient with LUTS indicate a UTI or prostatitis.

Initial imaging

- mpMRI of the prostate [19][20]

- Becoming the preferred imaging modality for suspected prostate cancer [19][21]

- Additional indications include:

- Guidance of prostate biopsy

- Clinical suspicion of prostate cancer despite negative transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) or TRUS-guided biopsy

- Initial staging of confirmed prostate cancer

- Active surveillance and follow-up

- Transrectal ultrasound of the prostate: predominantly used to guide prostate biopsy if there is clinical suspicion of prostate cancer [22][23]

Prostate biopsy

- Indication: clinical suspicion of prostate cancer after shared decision-making with a patient whose life expectancy is ≥ 10 years [8][24]

- Important considerations: Consider the following to minimize unnecessary biopsies. [8]

- Adjunctive PSA tests

- Free PSA:total PSA ratio of < 10–20% suggests a high probability of prostate cancer. [25]

- PSA density [26]

- Calculated by dividing total PSA by prostate volume (as determined on imaging)

- A low PSA density (< 0.08 ng/mL/cc) suggests that clinically significant cancer is unlikely.

- mpMRI of the prostate (if not already performed)

- Presence of risk factors for prostate cancer

- Prostate cancer antigen 3 gene (PCA3) levels in urine [27]

- Adjunctive PSA tests

- Technique

- Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent prostatitis: recommended for transrectal biopsy; consider before transperineal biopsy

- Anesthesia: local anesthesia, nerve blocks, procedural sedation, or general anesthesia

- Under image guidance (TRUS-guided or MRI-guided), several biopsy cores are obtained from the prostate via the transperineal or transrectal approach. [28][29]

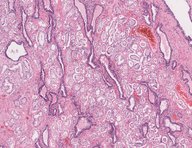

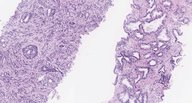

- Findings: adenocarcinoma [30][31]

- Gleason grade (Gleason pattern): depending on the degree of differentiation of tumor cells and stromal invasion, tumors are graded from 1 (well-differentiated) to 5 (poorly differentiated)

- Gleason score (ranges from 2 to 10): the sum of the two most prevalent Gleason grades [32]

- Grade groups: prognostic categories based on the Gleason score that are used to guide management [31]

Evaluation of tumor extent [21][22][33]

- mpMRI provides information on local tumor extent (e.g., tumor size and volume).

- Additional imaging to assess for local tumor extent and metastasis to guide management: [21]

- Recommended in patients with intermediate or high-risk prostate cancer (i.e., patients with PSA > 10 ng/mL and an unfavorable grade group

- Not routinely recommended for patients with low or very low-risk prostate cancer (i.e., patients with PSA < 10 ng/mL, a favorable grade group, and low tumor burden in biopsy cores)

- Cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI, or PET-CT scan) is recommended to identify: [34][35]

- The spread of cancer beyond the prostatic capsule

- Pelvic and distal lymph node involvement

- Hepatic and osseous metastasis

- Assessment of bone metastases

- Serum alkaline phosphatase may be elevated in bone metastases.

- Bone scintigraphy (technetium-99m) is the standard study for detecting bone metastases. [22]

- PET scan is more sensitive than bone scintigraphy and may become the new standard. [22][36]

- X-rays (e.g., spinal x-ray) may be appropriate to evaluate undifferentiated bone pain or if pathological fractures are suspected.

Staging

- Localized prostate cancer

- Tumor confined to the prostate (T1–T2) or tumor with extracapsular extension (T3a)

- And no evidence of lymph node involvement or metastasis (i.e., N0, M0)

- Locally advanced prostate cancer [39]

- Extension to the seminal vesicles (T3b) or adjacent periprostatic tissue (T4)

- Or regional lymph node involvement (N1) [38]

- And no evidence of distant metastases (M0)

- Metastatic prostate cancer

- Involvement of lymph nodes outside the true pelvis (M1a)

- Or spread to nonnodal regions (M1b–c)

- Most common site: bone (M1b), especially the vertebrae

- Less common sites: lungs, liver, and adrenal glands (M1c)

Management

Approach [21][33]

- Estimate the patient's life expectancy.

- Limited life expectancy (≤ 5 years): Consider watchful waiting (asymptomatic patients) or palliative ADT (symptomatic patients). [21]

- Life expectancy > 5 years: Manage according to cancer stage.

- Stage prostate cancer to determine if it is localized, locally advanced, or metastatic.

- Localized prostate cancer: Stratify risk based on the histological grade group and pretreatment PSA levels.

- Low or very low-risk prostate cancer: Consider active surveillance.

- Intermediate or high-risk prostate cancer: radical prostatectomy OR radiotherapy in combination with ADT

- Locally advanced prostate cancer: ADT PLUS androgen synthesis inhibitor PLUS radiation therapy

- Metastatic prostate cancer

- Management is similar to that of locally advanced prostate cancer.

- Antiandrogens or chemotherapy can be considered instead of androgen synthesis inhibitors.

- Localized prostate cancer: Stratify risk based on the histological grade group and pretreatment PSA levels.

- Anticipate and manage treatment-related complications (e.g., osteoporosis, pathological fractures, erectile dysfunction).

- Schedule follow-ups to assess response to therapy.

Watchful waiting [21]

- Indications: recommended approach if all of the following apply

- Limited life expectancy (≤ 5 years)

- Slow-growing tumor (i.e., low-risk or intermediate-risk localized tumors)

- Asymptomatic or minimal symptoms

- Method

- Regular monitoring with scheduled DRE and serum PSA levels (less intensive follow-up than active surveillance).

- Initiate definitive management according to cancer stage only when symptoms occur.

Active surveillance [21][40]

- Indications [21]

- Very low-risk and low-risk localized prostate cancers in patients with a life expectancy > 5 years

- May be considered in favorable intermediate-risk localized prostate cancer

- Method

- Regular monitoring with scheduled DRE, PSA, prostate biopsies, and mpMRI

- Initiate definitive management according to cancer stage if disease progression is demonstrated.

Androgen deprivation [33][41]

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

- Definition: therapy designed to decrease testosterone production by the testes

- Indications

- Locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer: primary treatment modality

- High-risk localized prostate cancer: alternative to radical prostatectomy

- Options

- Medical castration: decreases pituitary stimulation of androgen production by the testes

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (e.g., leuprolide)

- Gonadotropin-releasing antagonist (e.g., degarelix)

- GnRH receptor antagonist (e.g., relugolix)

- Surgical castration: bilateral orchiectomy

- Medical castration: decreases pituitary stimulation of androgen production by the testes

- Adverse effects

- Increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures

- Sexual dysfunction: loss of libido, erectile dysfunction

- Change in body image: gynecomastia, weight gain, decreased penile and testicular size

- Change in body composition: increased body fat, decreased muscle mass

- Increased cardiovascular and metabolic risk

- Anemia

Androgen synthesis inhibitors and androgen receptor antagonists [42]

- Indication: adjunct to ADT in locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer

- Androgen synthesis inhibitors

- Mechanism of action: inhibition of CYP17 gene products (including 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase) → inhibits androgen synthesis in the adrenal glands, testis, and tumor tissue

- Commonly used agent: abiraterone

- Specific adverse effects:

- Increased production of mineralocorticoids: hypertension, hypokalemia, cardiac arrhythmias

- Inhibition of glucocorticoid production: adrenal insufficiency

- Important consideration

- Glucocorticoids should be coadministered to avoid adrenal insufficiency.

- Glucocorticoids further increase bone fragility associated with androgen deprivation and aging.

- Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogen therapy)

- Mechanism of action: displaces androgens from androgen receptors

- Commonly used agents: apalutamide and enzalutamide (second-generation antiandrogens) [43]

Radiation therapy [21][44]

- Indications

- Localized prostate cancer: primary treatment option

- Metastatic prostate cancer, high-risk localized prostate cancer, local recurrence following prostatectomy: as an adjunct to androgen deprivation

- After prostatectomy: adjuvant therapy if adverse features are detected

- Options: brachytherapy and/or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

- Complications

- Radiation proctitis, enteritis (e.g., diarrhea),

- Cystitis, urethritis, and urinary incontinence

- Erectile dysfunction [45]

- Increased risk of rectal cancer [46]

Radical prostatectomy [21]

- Indications

- Localized prostate cancer in patients who are not candidates for active surveillance

- Following unsuccessful primary radiation therapy (salvage prostatectomy) [47]

- Technique

- Removal of the entire prostate gland, including the prostatic capsule, the seminal vesicles, and the vas deferens [21]

- Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed during prostatectomy.

- Important consideration: PSA levels should drop to undetectable levels after a successful prostatectomy.

- Complications: erectile dysfunction , urinary incontinence , infertility [45]

Chemotherapy [33]

- Indication: Consider as an adjunct to ADT in patients with metastatic prostate cancer.

- Commonly used agent: docetaxel (a cytotoxic agent)

Management of bone health [48][49][50]

Prophylaxis against treatment-induced osteoporosis and fractures

- Indications: patients on ADT, antiandrogens, and/or glucocorticoids

- Method

- Optimize bone health (see “Treatment of osteoporosis” for details).

- Assess fracture risk

- Consider osteoclast inhibitors (e.g., bisphosphonates, denosumab) in patients at high risk of a skeletal-related event.

- See “Pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis” for details and dosages.

Management of skeletal events [51]

- Pain due to skeletal metastases: Consider EBRT.

- Acute skeletal pain: urgent x-rays to assess for pathological fractures

- New neurological symptoms: urgent MRI spine to identify spinal cord compression (see “Acute back pain” for details)

Follow-up

- Monitor serum total PSA levels. [52]

- Every 6 months for the first 5 years, then annually for patients who have had definitive local therapy

- Every 3–6 months for patients on ADT

- Consider assessing PSA velocity (PSA doubling time); a significant rise or short doubling time suggests a recurrence. [11]

- Arrange further studies for patients with abnormal PSA values.

- After radical prostatectomy: Any measurable PSA value should prompt evaluation for recurrence.

- After radiation therapy: Any rise in PSA from nadir should prompt evaluation for recurrence. [52]

- Annual DRE: to monitor for prostate cancer recurrence and rectal cancer [46]

Screening

General principles [53]

- PSA screening is controversial as it has:

- A high false-positive rate [53]

- A high detection rate of clinically insignificant cancers (leading to overdiagnosis) [53]

- Minimal or no effect on prostate cancer-related mortality. [55][56][57]

- Patient harm may occur as a result of testing and/or treatment initiated by a positive PSA screening test.

Screening recommendations [54][58]

- Recommendations for screening are based on age and life expectancy and differ between the USPSTF and AUA. [54][58]

- USPSTF: Offer screening to all individuals between 55 and 69 years.

- AUA

- Offer screening to all individuals aged 45–69 years.

- Consider initiating screening at age 40 years for individuals with risk factors for prostate cancer.

- Screening is not recommended for patients with a life expectancy < 10 years. [58]

Screening modalities [6][58]

- PSA level remains the standard screening tool.

- The PSA threshold for referral and biopsy is based on age. [58]

- Lower thresholds are used in:

- Patients receiving a 5-ARI [59]

- Patients receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy (see “Preventive health care of transgender individuals”)

- DRE is not recommended as the sole screening tool for prostate cancer. [60]

- A screening interval of 2 years (or more) is recommended.

Prognosis

- The most important prognostic indicator for prostate cancer is the histological grade (i.e., grade group or Gleason score). [38]

- Broadly, patients with cancer confined to the prostate and pretreatment PSA levels < 10 ng/mL have a favorable prognosis. [21][61]

| Grade groups for prostate cancer [31][62] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Grade group | Gleason score [32] | 5-year survival after radical prostatectomy |

| 1 | ≤ 6 | 96% |

| 2 | 3 + 4 = 7 | 88% |

| 3 | 4 + 3 = 7 | 63% |

| 4 | 4 + 4 = 8 | 48% |

| 5 | 9 or 10 | 26% |

Differential diagnoses

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Prostatitis

- Other tumors of the prostate

Related One-Minute Telegram

- One-Minute Telegram 72-2023-3/3: Aggressive therapy may not be the key to survival for localized prostate cancer

Tips and Links

- 2021 AUA Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline

- 2019 AUA Adjuvant and Salvage Radiotherapy After Prostatectomy: ASTRO/AUA Guideline

- 2017 AUA Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/Astro/SUO Guideline

- US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations (Prostate cancer)

- Sign up for the One-Minute Telegram

Comments

Post a Comment